Ralph Loop with Google ADK: AI Agents That Verify, Not Guess

Thomas Chong

2026-01-08

Every developer has experienced this: you ask an AI to write a Dockerfile, it confidently delivers something that looks correct, and then docker build fails. The AI thought it was done. It wasn't.

The Ralph Loop pattern offers a different philosophy: don't trust the AI to judge its own work—make it prove success through external verification.

Originally defined by Geoffrey Huntley, Ralph Loop in its purest form is simply a bash loop: while :; do cat PROMPT.md | <ANY_CODING_AGENT> ; done. The pattern keeps running until objective criteria confirm the task is actually complete—not when the LLM says "this looks good," but when docker build succeeds, docker run starts the container, and the health check passes.

Named after Ralph Wiggum from The Simpsons (persistently wrong but never giving up), the philosophy is: "It's better to fail predictably than succeed unpredictably."

In this tutorial, we'll implement Ralph Loop using Google ADK that generates production-ready Dockerfiles—and keeps iterating until Docker itself confirms it works.

1. The Problem: LLMs Grading Their Own Homework (And Why Normal Loops Don't Solve It)

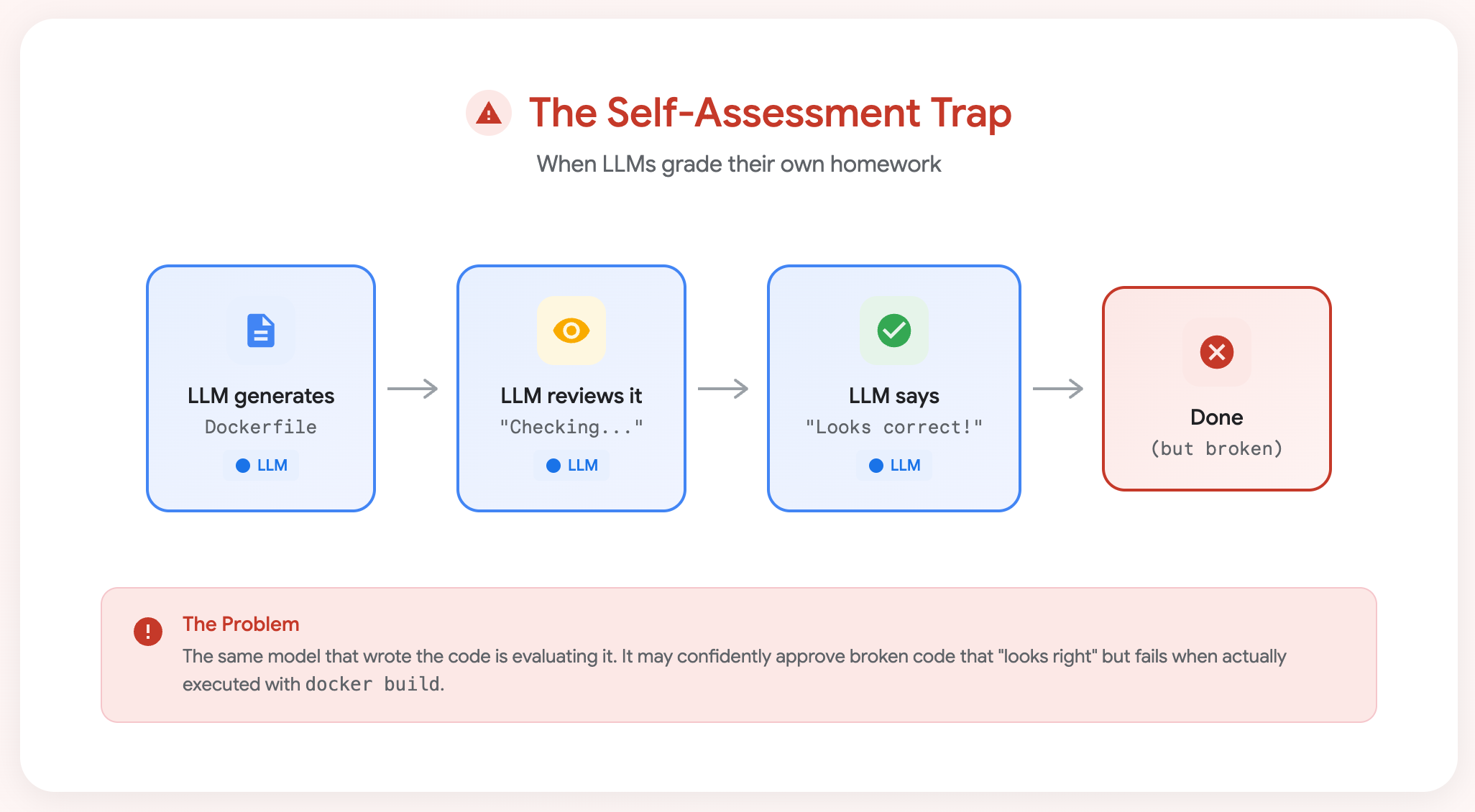

The Self-Assessment Trap

Standard agentic loops work like this:

The self-assessment trap: The same model that wrote the code is evaluating it—and may confidently approve broken code.

But here's the trap: even with Google ADK's LoopAgent, you can accidentally create the same problem if the LLM decides when to stop.

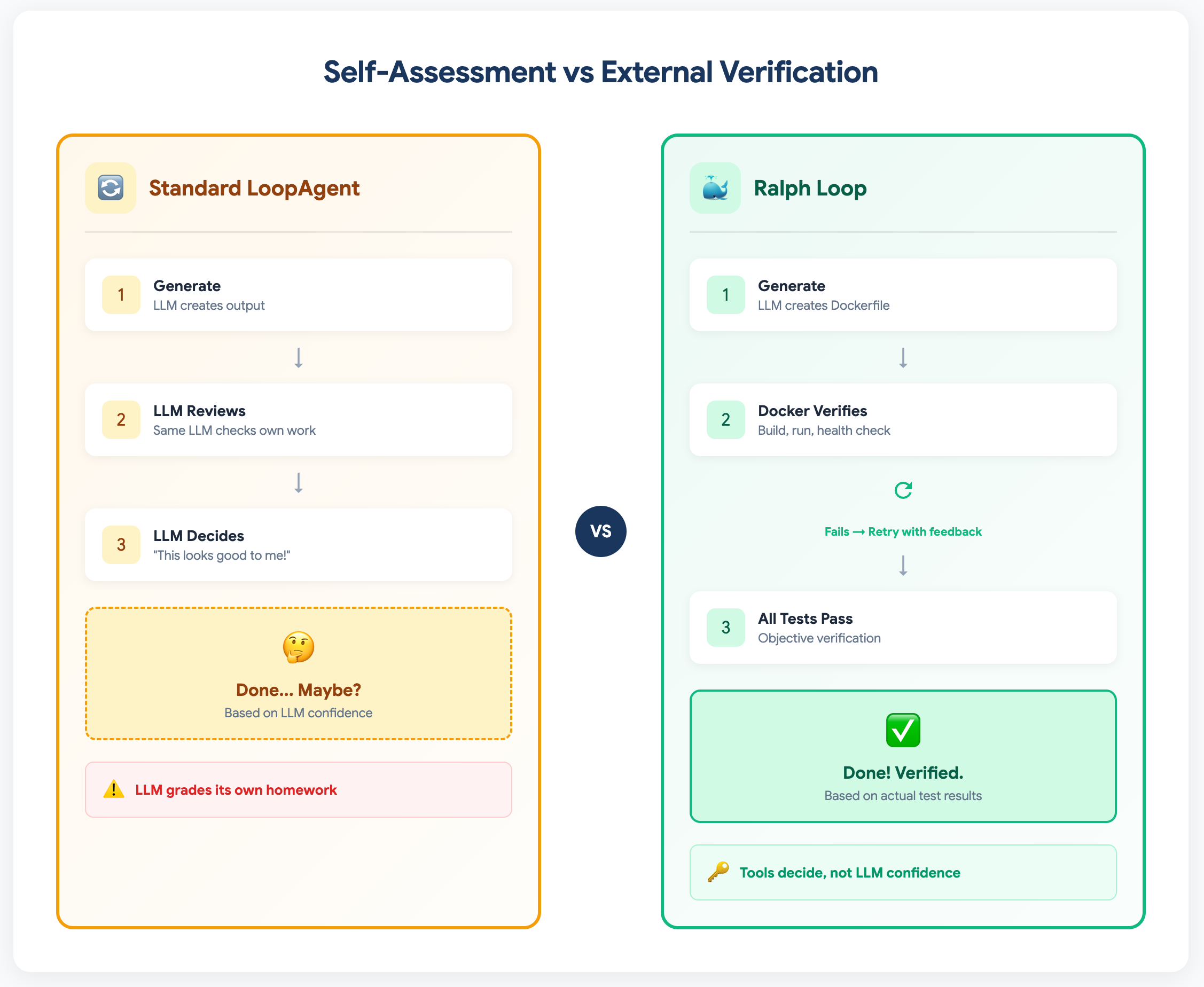

Normal Agent Loop vs Ralph Loop

Google ADK's LoopAgent is a powerful primitive—it repeats sub-agents until exit_loop() is called. But what triggers exit_loop() makes all the difference:

| Approach | What Decides "Done"? | Result | |----------|---------------------|--------| | Self-Assessment Loop | LLM reviews its own output | May stop with broken code that "looks right" | | Ralph Loop | External tool (Docker, compiler, tests) | Only stops when code actually works |

# ❌ Self-assessment: LLM grades its own work

verification_agent = Agent(

instruction="""Review the Dockerfile.

If YOU think it looks correct, call exit_loop().""",

tools=[exit_loop]

)

# ✅ Ralph Loop: External verification decides

verification_agent = Agent(

instruction="""Check the Docker verification result.

If all_stages_passed is True (set by Docker tools), call exit_loop().

If False, the Docker error tells us what to fix.""",

tools=[exit_loop]

)

The key insight: In a Ralph Loop, the exit_loop() decision is driven by results from external tools (Docker build, run, health check), not by the LLM's opinion of its own work.

The key difference: Standard loops let the LLM grade its own work. Ralph Loop uses external tools (like Docker) to verify success objectively.

Research supports this approach. A 2024 MIT survey on LLM self-correction found that self-correction works well "in tasks that can use reliable external feedback" but struggles when LLMs must evaluate their own outputs.

2. Why Dockerfile Generation is Perfect for Ralph Loop

Dockerfile generation is an ideal candidate for Ralph Loop because it combines common LLM failure modes with clear, objective verification:

| Characteristic | Why It Matters | |----------------|----------------| | LLMs make real mistakes | Missing dependencies, wrong CMD syntax, COPY order issues | | Verification is objective | Build either succeeds or fails—no ambiguity | | Feedback is actionable | Docker errors tell you exactly what's wrong | | Multiple failure modes | Lint → Build → Run → Health → Functional | | Universally relatable | Every developer uses Docker |

A Dockerfile that "looks correct" to an LLM might:

- Forget system dependencies for Python packages

- Use the wrong CMD syntax

- Miss the

--host 0.0.0.0for uvicorn - Copy files in the wrong order

Only actually running docker build and docker run catches these issues.

Now that we understand why Dockerfile generation is perfect for Ralph Loop, let's build it. We'll use Google ADK with Gemini to create an agent that generates Dockerfiles—and keeps iterating until Docker confirms they work.

3. Setup: Google ADK and Gemini 3

Prerequisites

# Docker must be installed and running

docker --version

# Create virtual environment

python -m venv .venv

source .venv/bin/activate # macOS/Linux

# Install dependencies

pip install google-adk python-dotenv requests Pillow

Configure API Access

Create a .env file:

GOOGLE_GENAI_USE_VERTEXAI=FALSE

GOOGLE_API_KEY=your_api_key_here

Project Structure

ralph_dockerfile_agent/

├── __init__.py

├── agent.py # ADK agent definitions

├── tools.py # Docker verification tools

└── app/ # The application to dockerize

├── main.py # FastAPI image resizer

├── requirements.txt

└── .dockerignore

4. The Application: A FastAPI Image Resizer

We'll generate a Dockerfile for a simple but realistic FastAPI app:

# app/main.py

from fastapi import FastAPI, UploadFile, HTTPException

from fastapi.responses import StreamingResponse

from PIL import Image

import io

app = FastAPI(title="Image Resizer API")

@app.get("/health")

def health_check():

"""Health check that verifies Pillow works."""

test_img = Image.new('RGB', (10, 10), color='red')

buffer = io.BytesIO()

test_img.save(buffer, format='PNG')

return {"status": "healthy", "pillow_version": Image.__version__}

@app.post("/resize")

async def resize_image(file: UploadFile, width: int = 100, height: int = 100):

"""Resize uploaded image to specified dimensions."""

contents = await file.read()

img = Image.open(io.BytesIO(contents))

resized = img.resize((width, height), Image.Resampling.LANCZOS)

output = io.BytesIO()

resized.save(output, format=img.format or "PNG")

output.seek(0)

return StreamingResponse(output, media_type=file.content_type)

Dependencies (app/requirements.txt):

fastapi==0.115.6

uvicorn[standard]==0.34.0

Pillow==11.1.0

python-multipart==0.0.20

This app is perfect because:

- Pillow may require system dependencies (potential build failure)

- Health check verifies Pillow actually works (not just installed)

- File upload tests real functionality

With our application ready, we need to build the verification pipeline—the component that makes Ralph Loop actually work. This is what distinguishes Ralph Loop from simple retry logic: structured, external feedback.

5. The Heart of Ralph Loop: External Verification

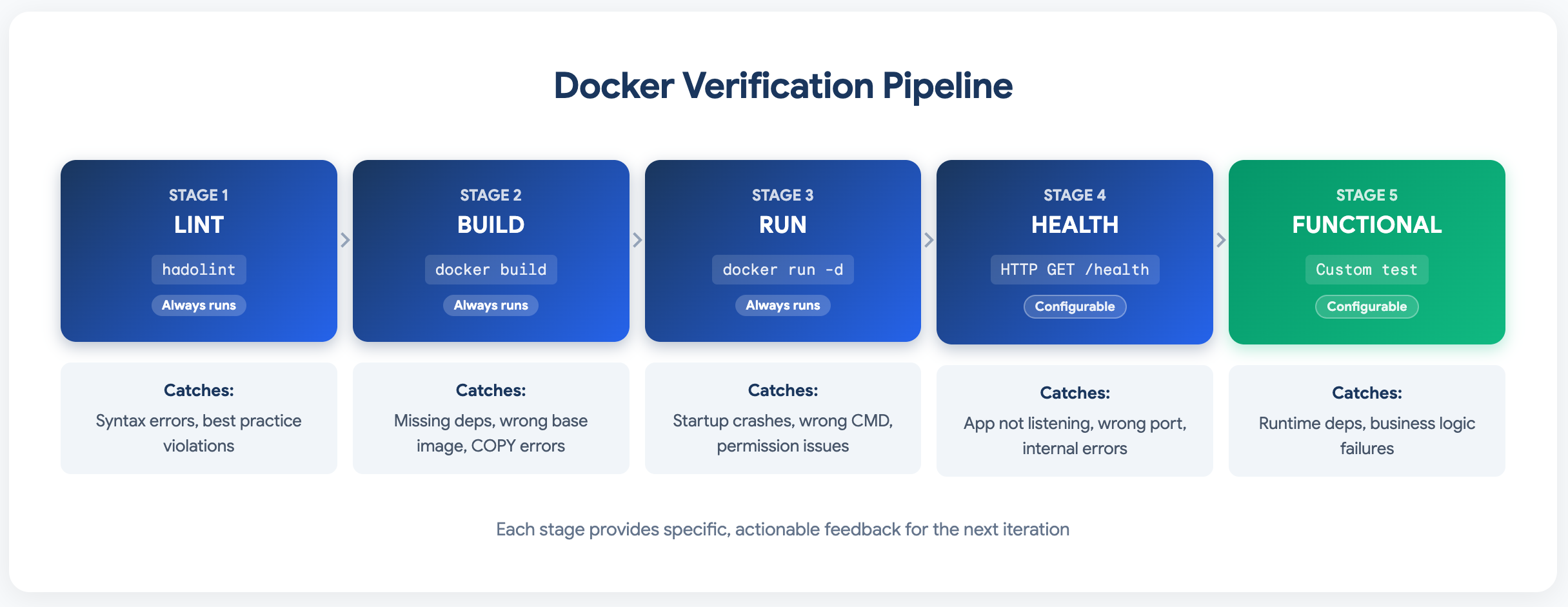

The verification tool runs a configurable 5-stage pipeline using real Docker commands:

# tools.py - Generic Docker verification

@dataclass

class VerificationConfig:

"""Configuration for Docker verification pipeline."""

app_directory: str

container_port: int = 8000

health_endpoint: Optional[str] = "/health" # None to skip

functional_test: Optional[dict] = None # Custom test config

def verify_dockerfile(dockerfile_content: str, tool_context: ToolContext) -> dict:

"""

EXTERNAL VERIFICATION: Docker tools verify the Dockerfile.

Not LLM judgment—actual docker build/run/health check.

"""

# Configuration loaded from state - makes tools reusable

config = get_config_from_state(tool_context)

verifier = DockerVerifier(config)

result = verifier.verify(dockerfile_content)

# Store result in state for other agents to access

tool_context.state["all_stages_passed"] = (result["status"] == "ALL_PASSED")

return result

The Verification Pipeline

The 5-stage verification pipeline: Each stage catches different types of errors and provides specific, actionable feedback.

Note: Stages 1-3 are universal for any Docker deployment. Stages 4-5 are optional and configurable via state, making these tools reusable across different applications.

Each stage provides specific, actionable feedback that the LLM can use to fix the Dockerfile.

Now that we have our verification pipeline, let's design the agent structure. The key architectural decision is how to orchestrate the generation-verification-refinement cycle.

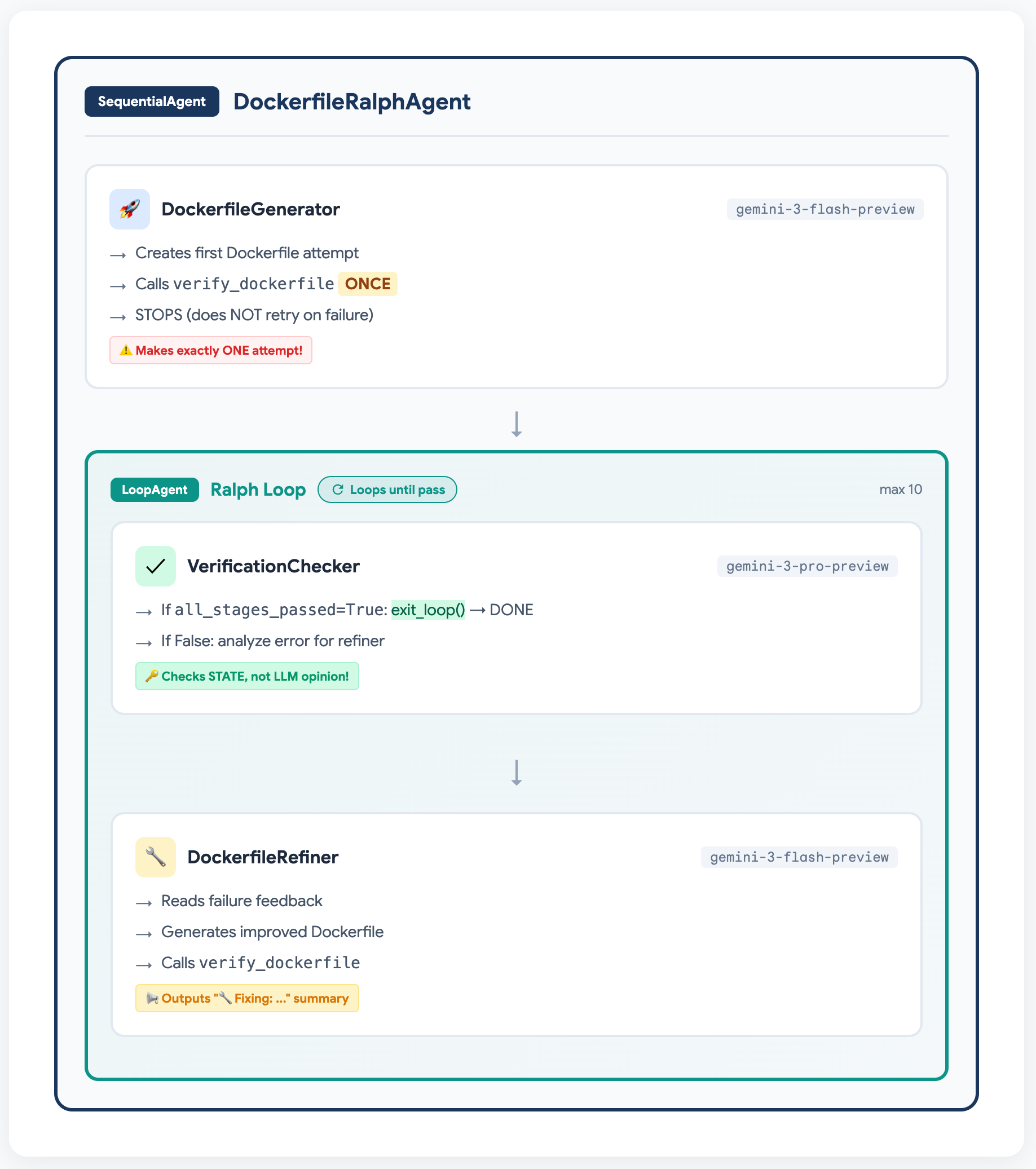

6. Agent Architecture

The Flow: Why Each Agent Exists

The agent hierarchy: DockerfileGenerator makes one attempt, then the Ralph Loop iterates until Docker verification passes.

Why Three Agents?

We split the workflow into three specialized agents, each with a distinct role:

| Agent | Purpose | Key Trick |

|-------|---------|-----------|

| DockerfileGenerator | Initial attempt | Limited to ONE try (prevents self-loop) |

| VerificationChecker | Exit decision | Checks state["all_stages_passed"], NOT LLM judgment |

| DockerfileRefiner | Iterative fixes | Shows visible "🔧 Fixing: ..." before each fix |

This separation ensures:

- The loop structure actually gets used (not bypassed by agent self-retry)

- Exit decisions are objective (state-driven, not LLM-driven)

- Users can see what's happening at each iteration

7. ADK Implementation: Structuring the Agent Flow

When implementing Ralph Loop in Google ADK, we face an architectural decision: how do we structure the agent flow?

Option A: Single Agent Does Everything

The simplest approach—one agent that generates, verifies, and refines:

# Simple but less observable

single_agent = Agent(

instruction="""Generate a Dockerfile and verify it works.

If it fails, analyze the error and try again until it passes.""",

tools=[verify_dockerfile]

)

This works! The agent will iterate until Docker verification passes. This is actually a valid Ralph Loop implementation—external verification still decides success.

Option B: Multi-Agent with Visible Iterations (Our Choice)

For observability and debugging, we chose to separate agents:

# More verbose but easier to debug and observe

initial_generator = Agent(...) # First attempt

verification_checker = Agent(...) # Check result, call exit_loop if done

refinement_agent = Agent(...) # Fix issues, show "🔧 Fixing: ..." messages

Why we chose this:

- ✅ Each iteration is visible in the UI (great for demos and debugging)

- ✅ Clear separation: who generates vs. who decides vs. who refines

- ✅ The "🔧 Fixing: ..." summaries show users what's happening

- ✅ Easier to tune individual agent prompts

The tradeoff:

- More complex setup

- Need to ensure agents don't overlap (e.g., generator trying to fix its own errors)

Ensuring Clean Handoffs in Multi-Agent Setup

When using multiple agents, we tell the initial generator to make one attempt and stop:

initial_generator = Agent(

instruction="""Generate a Dockerfile and verify it.

After calling verify_dockerfile once, output your Dockerfile and stop.

Another agent will handle refinements if needed.""",

tools=[verify_dockerfile]

)

This isn't a "trick" or limitation—it's an architectural choice to ensure clean handoffs between agents. The core Ralph Loop principle (external verification) works either way.

Which Approach Should You Use?

The choice between single-agent and multi-agent depends on your priorities:

| Approach | When to Use | |----------|-------------| | Single Agent | Simple tasks, production pipelines where observability is less critical | | Multi-Agent | Demos, debugging, complex tasks where you want to see each step |

Both are valid Ralph Loop implementations. The key is that Docker verification decides when you're done, not the LLM's confidence.

With the architecture decided, here's the complete implementation. Pay attention to the agent instructions—they're carefully crafted to ensure clean handoffs and visible iteration summaries.

8. The Agent Code

# agent.py

from google.adk.agents import Agent, LoopAgent, SequentialAgent

from .tools import verify_dockerfile, exit_loop

GEMINI_FLASH = "gemini-3-flash-preview"

GEMINI_PRO = "gemini-3-pro-preview"

# Initial Generator - NOTE: Limited to ONE attempt!

initial_generator = Agent(

name="DockerfileGenerator",

model=GEMINI_FLASH,

instruction="""You are a Docker expert. Generate a Dockerfile for a Python web application.

**What you know:**

- Entry point: main.py

- Dependencies are listed in requirements.txt

- The app runs as a web server on port 8000

**CRITICAL: Make exactly ONE attempt.**

- Call verify_dockerfile ONCE with your best Dockerfile

- Do NOT retry if it fails - the refinement loop will handle fixes

- After calling verify_dockerfile once, STOP and output your Dockerfile

This is your ONLY chance. Another agent will handle any fixes needed.""",

tools=[verify_dockerfile],

output_key="current_dockerfile"

)

# Verification Decision Agent - Uses EXTERNAL state, not LLM judgment

verification_agent = Agent(

name="VerificationChecker",

model=GEMINI_PRO, # Stronger model for decision logic

instruction="""You are a verification decision agent in a Ralph Loop.

Look at the previous verification result from the conversation history.

**Your Task:**

If the verification shows status "ALL_PASSED" or all_stages_passed is True:

→ Call exit_loop() immediately. The Dockerfile works!

If the verification failed:

→ Analyze what failed from the verification result

→ Provide a clear summary of:

1. Which stage failed (lint/build/run/health/functional)

2. The specific error message

3. What needs to be fixed

→ Do NOT call exit_loop - let the refinement agent fix it""",

tools=[exit_loop]

)

# Refinement Agent - Shows what it's fixing BEFORE fixing it

refinement_agent = Agent(

name="DockerfileRefiner",

model=GEMINI_FLASH,

instruction="""You are a Docker expert fixing a Dockerfile that failed verification.

**Your Task - IMPORTANT: Output a summary BEFORE fixing:**

1. First, OUTPUT a brief summary message like:

"🔧 **Fixing:** [describe the error]

**Solution:** [describe what you're adding/changing]"

2. Then generate an IMPROVED Dockerfile that fixes the specific issue

3. Call verify_dockerfile with your improved Dockerfile

**Common Fixes:**

- "environment variable is required" → Add ENV statement

- "directory does not exist" → Add RUN mkdir -p

- "pip install failed" → Add system dependencies (apt-get install)

- "Connection refused" → Check EXPOSE and uvicorn command

Always explain what you're fixing, then call verify_dockerfile to test it.""",

tools=[verify_dockerfile],

output_key="current_dockerfile"

)

# The Ralph Loop

ralph_loop = LoopAgent(

name="RalphLoop",

max_iterations=10,

sub_agents=[verification_agent, refinement_agent]

)

# Root Agent

root_agent = SequentialAgent(

name="DockerfileRalphAgent",

sub_agents=[initial_generator, ralph_loop]

)

# Initialize session state with configuration

def initialize_session(session):

"""Configure the verification pipeline via state."""

session.state["app_directory"] = "./app" # Path to app

session.state["container_port"] = 8000

session.state["health_endpoint"] = "/health"

# Optional: configure custom functional test

session.state["functional_test_config"] = {

"method": "POST",

"endpoint": "/resize",

"params": {"width": 50, "height": 50},

"files": {"file": ("test.png", test_image_bytes, "image/png")},

"expected_status": 200

}

9. Running the Agent

# Start ADK web UI

adk web ralph_dockerfile_agent

Navigate to http://localhost:8888 and watch the magic happen.

10. What You'll See: A Real Iteration Sequence

Let's walk through a real execution. The agent will attempt to generate a Dockerfile, and you'll see how Docker feedback drives each iteration until success.

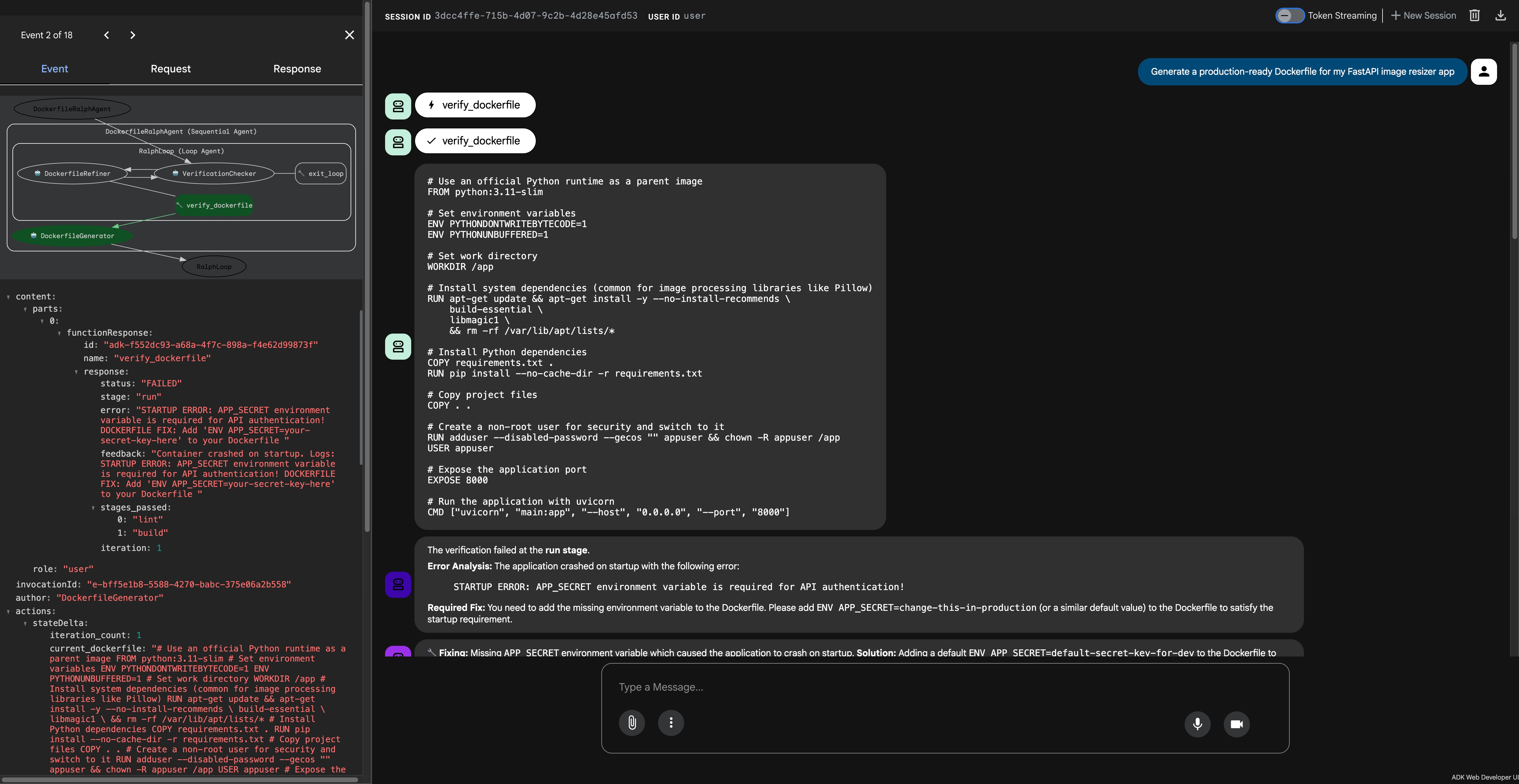

Here's what a real run looks like in the ADK Web UI. The first screenshot shows the initial Dockerfile attempt and the first failure:

ADK Web UI: The initial Dockerfile attempt fails with "APP_SECRET environment variable is required"—the first of several missing requirements.

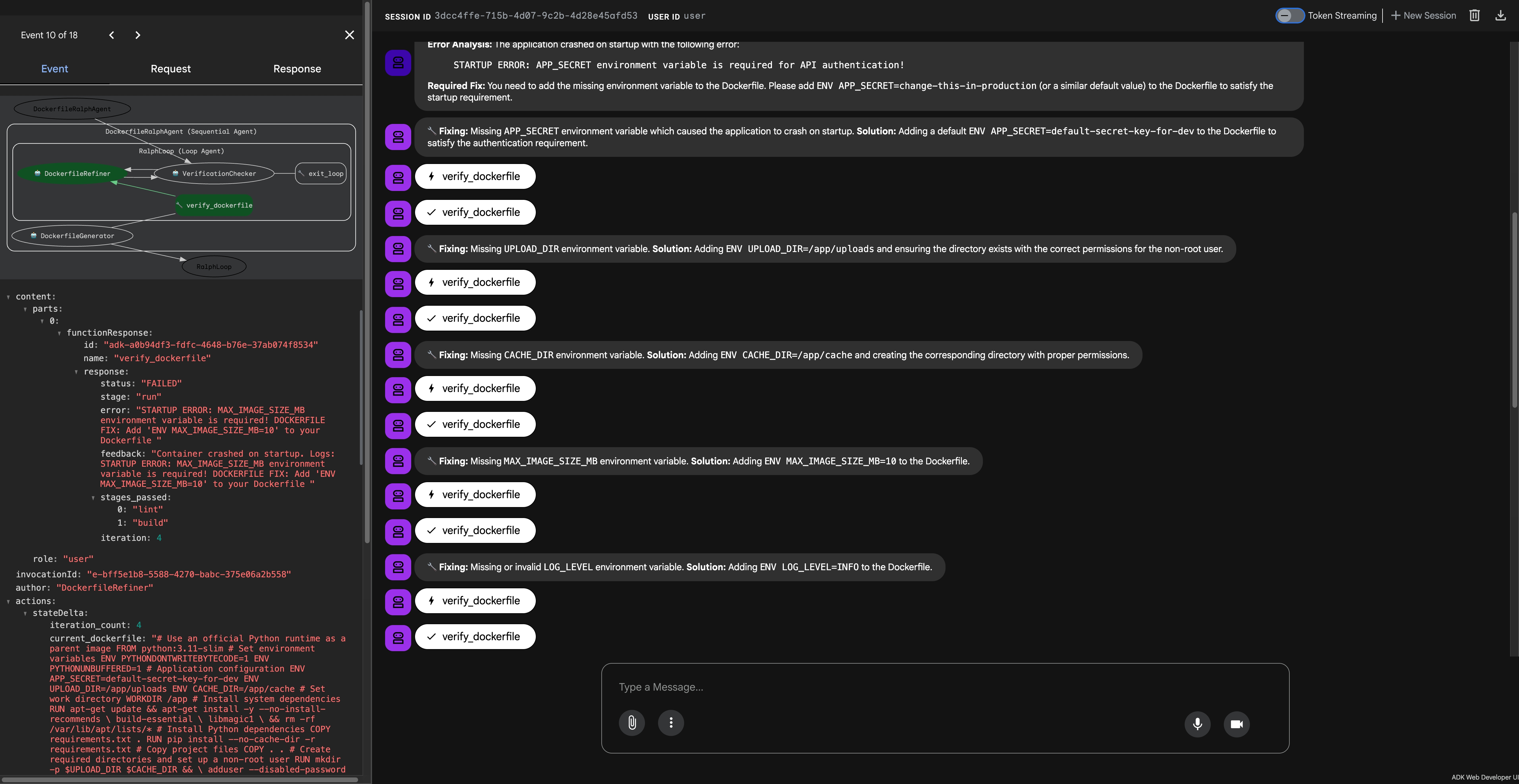

Notice the visible summary messages showing what's being fixed at each step:

Each iteration shows a "🔧 Fixing:" summary before applying the fix, making the refinement process visible and debuggable.

Iteration 1: Initial Attempt (DockerfileGenerator)

The initial generator creates a Dockerfile with Python best practices—but Docker reveals the first missing requirement:

[DockerfileGenerator] → verify_dockerfile

Status: FAILED, Stage: run

Error: "STARTUP ERROR: APP_SECRET environment variable is required for API authentication!"

Iterations 2-6: The Ralph Loop in Action (DockerfileRefiner)

Each iteration shows a visible summary message before applying the fix:

[Iteration 2 - DockerfileRefiner]

🔧 Fixing: Missing APP_SECRET environment variable which caused the application to crash on startup.

Solution: Adding a default ENV APP_SECRET=default-secret-key-for-dev to the Dockerfile.

→ verify_dockerfile → FAILED (UPLOAD_DIR required)

[Iteration 3 - DockerfileRefiner]

🔧 Fixing: Missing UPLOAD_DIR environment variable.

Solution: Adding ENV UPLOAD_DIR=/app/uploads and ensuring the directory exists.

→ verify_dockerfile → FAILED (CACHE_DIR required)

[Iteration 4 - DockerfileRefiner]

🔧 Fixing: Missing CACHE_DIR environment variable.

Solution: Adding ENV CACHE_DIR=/app/cache and creating the directory with proper permissions.

→ verify_dockerfile → FAILED (MAX_IMAGE_SIZE_MB required)

[Iteration 5 - DockerfileRefiner]

🔧 Fixing: Missing MAX_IMAGE_SIZE_MB environment variable.

Solution: Adding ENV MAX_IMAGE_SIZE_MB=10 to the Dockerfile.

→ verify_dockerfile → FAILED (LOG_LEVEL required)

[Iteration 6 - DockerfileRefiner]

🔧 Fixing: Missing or invalid LOG_LEVEL environment variable.

Solution: Adding ENV LOG_LEVEL=INFO to the Dockerfile.

→ verify_dockerfile → ALL_PASSED ✅

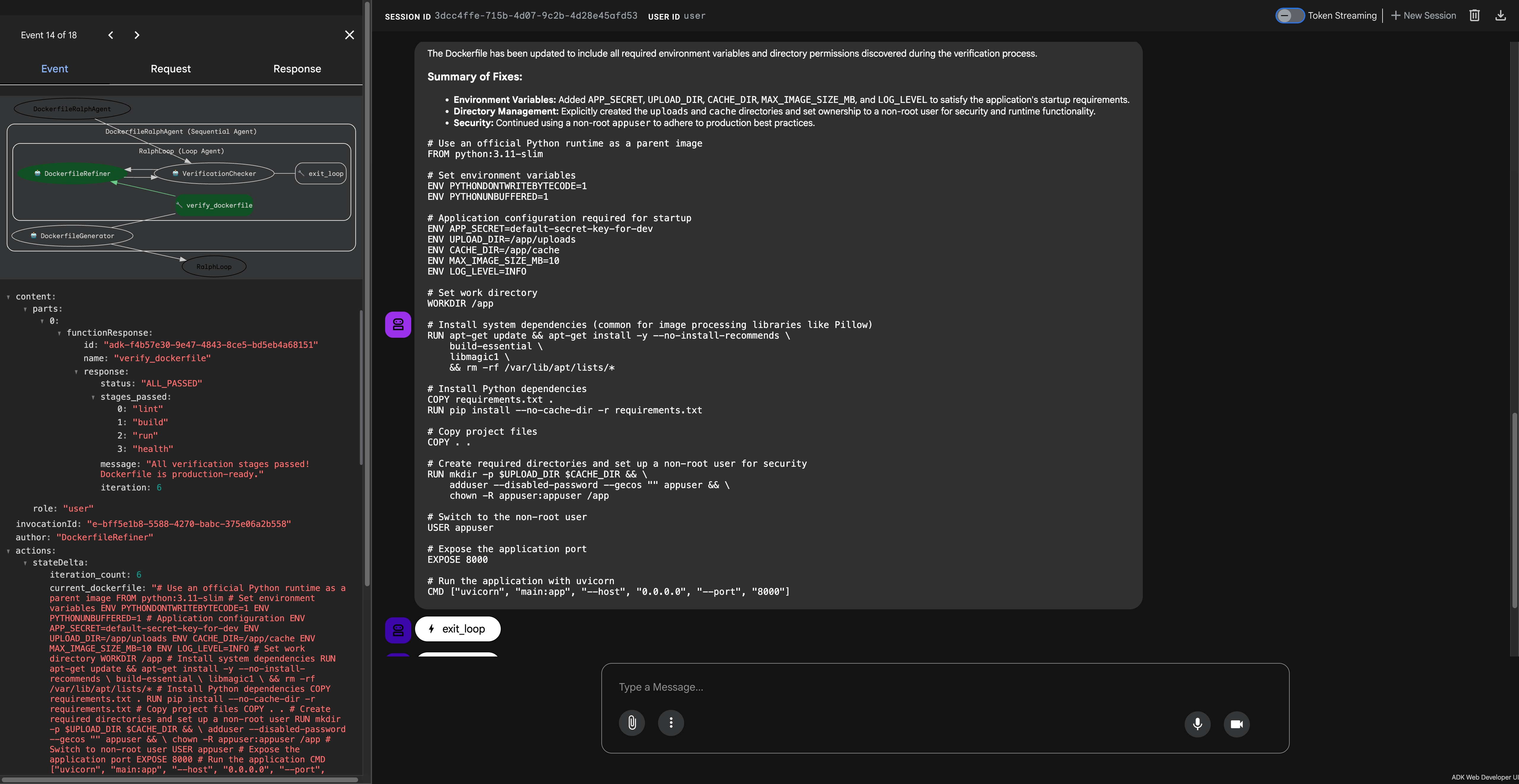

Final: VerificationChecker Calls exit_loop()

Once all_stages_passed is True in the state, the VerificationChecker immediately calls exit_loop():

[VerificationChecker]

→ exit_loop()

Response: {

"status": "COMPLETE",

"iterations_required": 6,

"message": "Dockerfile verified successfully after 6 iterations!"

}

The Final Dockerfile

# Use an official Python runtime as a parent image

FROM python:3.11-slim

# Set environment variables

ENV PYTHONDONTWRITEBYTECODE=1

ENV PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1

# Application configuration required for startup

ENV APP_SECRET=default-secret-key-for-dev

ENV UPLOAD_DIR=/app/uploads

ENV CACHE_DIR=/app/cache

ENV MAX_IMAGE_SIZE_MB=10

ENV LOG_LEVEL=INFO

# Set work directory

WORKDIR /app

# Install system dependencies (common for image processing libraries like Pillow)

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \

build-essential \

libmagic1 \

&& rm -rf /var/lib/apt/lists/*

# Install Python dependencies

COPY requirements.txt .

RUN pip install --no-cache-dir -r requirements.txt

# Copy project files

COPY . .

# Create required directories and set up a non-root user for security

RUN mkdir -p $UPLOAD_DIR $CACHE_DIR && \

adduser --disabled-password --gecos "" appuser && \

chown -R appuser:appuser /app

# Switch to the non-root user

USER appuser

# Expose the application port

EXPOSE 8000

# Run the application with uvicorn

CMD ["uvicorn", "main:app", "--host", "0.0.0.0", "--port", "8000"]

Success! After 6 iterations, all verification stages pass and the VerificationChecker calls exit_loop() to complete the task.

11. The Key Insights: What Makes Ralph Loop Different

Insight 1: External Verification, Not Self-Assessment

This is the single defining characteristic of Ralph Loop. Notice what happened:

- Iteration 1: LLM confidently generated a Dockerfile that "looked correct"

- Reality: Docker container crashed immediately

- Iterations 2-6: Each Docker error provided specific, actionable feedback

- Final: Only exited when Docker itself confirmed success

The LLM didn't grade its own homework. Docker did.

If the LLM had generated a perfect Dockerfile on the first try, the Ralph Loop would simply verify it and exit. The pattern doesn't artificially slow down success—it just ensures success is verified externally.

Insight 2: Feedback Injection on Failure

When verification fails, the feedback is injected back into the agent's context. This is how Ralph Loop differs from simple retry logic:

| Simple Retry | Ralph Loop | |--------------|------------| | Just runs again with same context | Injects failure reason as feedback | | Agent may repeat same mistake | Agent learns what specifically failed | | No structured improvement | Structured iteration toward success |

This pattern formalizes the concept: when verification returns { complete: false, reason: "..." }, the reason is injected as a user message for the next iteration.

Insight 3: The Philosophy

Ralph Loop inverts the usual AI coding workflow:

- Traditional: Carefully review each AI output, intervene on errors

- Ralph Loop: Define success criteria upfront (external verification), let the agent iterate toward them

Failures become data. Each iteration refines the approach based on what actually broke.

Demo Design: Sequential Error Discovery

For this tutorial, the application was designed with multiple sequential requirements to demonstrate multiple iterations:

# Each check runs in order - fail early, fix incrementally

startup_check(APP_SECRET is not None, "APP_SECRET required...") # Check 1

startup_check(UPLOAD_DIR is not None, "UPLOAD_DIR required...") # Check 2

startup_check(Path(UPLOAD_DIR).exists(), "Directory must exist...") # Check 3

startup_check(CACHE_DIR is not None, "CACHE_DIR required...") # Check 4

# ... and so on

This creates a natural iteration path where each fix reveals the next requirement. In real applications, your verification might pass on the first try—and that's perfectly fine! The Ralph Loop just ensures you verified it externally.

Having seen Ralph Loop in action, you might be tempted to apply it everywhere. But this pattern isn't universal—it has a critical prerequisite that determines whether it's the right tool for your task.

12. When to Use Ralph Loop (and Its Key Limitation)

⚠️ The Critical Requirement: Well-Defined Success Criteria

Ralph Loop only works when you can define objective, verifiable success criteria upfront.

This is the pattern's fundamental limitation. Before implementing Ralph Loop, ask yourself:

"Can I write a function that returns

truewhen the task is complete andfalsewhen it's not—without any LLM involvement in that decision?"

If the answer is no, Ralph Loop isn't the right pattern.

Examples of well-defined criteria:

- ✅

docker buildexits with code 0 - ✅ All pytest tests pass

- ✅ HTTP health check returns 200

- ✅ TypeScript compiles without errors

Examples of poorly-defined criteria:

- ❌ "The code looks clean"

- ❌ "The documentation is comprehensive"

- ❌ "The UI is user-friendly"

- ❌ "The response is helpful"

Without clear success criteria, the loop has no exit condition—or worse, it exits based on LLM self-assessment, defeating the entire purpose.

✅ Use Ralph Loop when:

- Output can be verified by external tools (compilers, test suites, validators)

- Success criteria are objective and binary

- Tasks are mechanical with clear pass/fail conditions

❌ Don't use Ralph Loop when:

- Quality is subjective (creative writing, design)

- No external verification is possible

- Tasks require human judgment

- Success criteria cannot be automated

Conclusion

TL;DR: What Makes Ralph Loop Work

The Ralph Loop pattern has one core principle: external verification decides when the task is complete, not the LLM's self-assessment.

| Aspect | Normal Agent | Ralph Loop | |--------|--------------|------------| | Who decides "done"? | LLM says "looks good" | External tool confirms success | | On failure? | May stop with broken output | Feedback injected, agent iterates | | Philosophy | Trust the AI | Trust the verification |

As Geoffrey Huntley originally defined it: Ralph is simply a bash loop that keeps running until the task actually works.

The Core Insight

If your agent can complete the task in zero-shot, excellent! The Ralph Loop doesn't prevent that. It simply ensures that success is verified externally rather than self-assessed. Docker doesn't care how confident the LLM was—it only cares if the container runs.

Google ADK Implementation Notes

In this tutorial, we used Google ADK's LoopAgent to implement Ralph Loop. A few ADK-specific patterns we used:

- State-driven exit: The

exit_loop()tool checksstate["all_stages_passed"]set by Docker verification - Feedback injection: Failed verification results are visible in conversation history for refinement

- Visible summaries: The refinement agent outputs "🔧 Fixing: ..." before each iteration for observability

These are implementation details for ADK, not core Ralph Loop requirements.

The Bottom Line

The Ralph Loop pattern shifts the paradigm from "AI confidence" to "verified correctness."

When you need code that actually works—not code that looks like it might work—let external tools be the judge. The Docker daemon doesn't care how confident the LLM was. It only cares if the Dockerfile builds and runs.

The AI's confidence doesn't matter. Only results do.

Resources

Have questions or want to share your Ralph Loop implementations? Connect with me on LinkedIn or leave a comment below!